In the frigid storage room of an old Alaskan military facility, researchers recently came across a sealed tin can of salmon, forgotten since 1973.

At first glance, it seemed like a typical piece of military surplus — but what was inside has sparked serious scientific interest across the world.

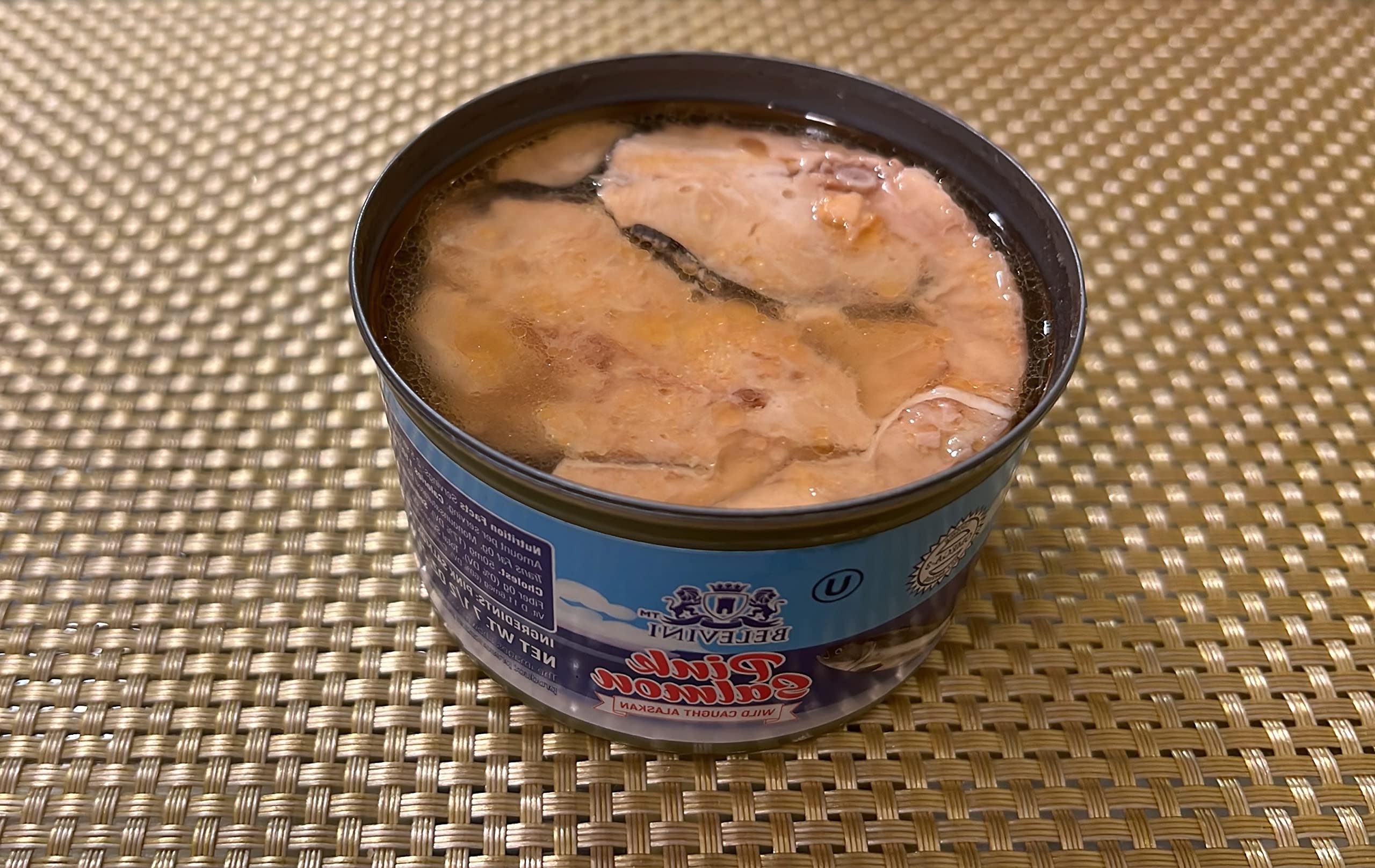

After half a century, the contents of the can were still intact. More than that: they showed no signs of spoilage, no abnormal odor, and a texture shockingly close to fresh. When tested, the salmon was not only still recognizable but contained nutrients and was technically safe to eat.

“We expected rust, rot, or at best, a degraded mass,” said microbiologist Lena Ross.

“Instead, we found something that challenged everything we thought we knew about long-term food preservation.”

The shocking truth behind a forgotten can

The salmon had been packed and stored during an era when oceans were cleaner, industrial additives were fewer, and manual quality checks were routine. Experts now believe three key factors made this discovery possible:

- Exceptionally pure ocean waters in the 1970s

- Slow, manual canning processes with minimal additives

- Constant low temperatures in the storage facility, around 4 °C

Laboratory tests found no microplastics, no heavy metals like mercury, and no dangerous bacteria — a near-impossible scenario for modern canned seafood. Even omega-3 levels and essential minerals were present in measurable amounts.

A time capsule from a healthier planet

To researchers, this isn’t just a story about a forgotten can. It’s a snapshot of what food, and our planet, used to be. Back then, industrial farming hadn’t yet altered the chemistry of wild fish, and packaging wasn’t dominated by plastic and artificial preservatives.

Today, most store-bought fish — especially farmed salmon — is raised on processed feeds, subjected to antibiotics, and packed using techniques designed more for shelf appeal than longevity. That 50-year-old can may have accidentally preserved something far more precious than salmon: environmental memory.

Global response: are there more cans like this?

Scientists from Norway, Japan, and Canada are now digging into their own archives to analyze long-forgotten military or emergency food reserves. The idea: can old food samples become ecological evidence of how our planet — and our food — has changed?

“These forgotten cans might tell us more about ocean health than any modern database,”

said one environmental biologist involved in a similar project in Sweden.

Some researchers are calling for the creation of a global archive of historic food samples, which could help track shifts in ocean contamination, soil mineral levels, and even packaging toxins. In other words, the future of food science might be hiding in dusty old boxes, waiting to be opened.

And if this can is any sign, the results could shake up what we think we know about preservation — and the state of our environment.